Berlin designer Tina Roeder bucks the trends

Authentic Self

In the early 2000s, as she was wrapping up her studies at Design Academy Eindhoven and establishing her own studio in Berlin, Tina Roeder was set to be a break-out design star. A piece from her White Billion Chairs (2002/2009) project—a series of 33 found monobloc chairs, customized with up to 10,000 hand-drilled holes each—was purchased by Vitra Design Museum for its permanent collection. She was turning some of the industry’s most important heads, as she got picked up by Gallery Fumi in London and was featured in magazine spreads alongside the likes of Martino Gamper and the Campana brothers. But instead of heeding the siren call of the limelight, this now mid-career designer followed her instincts along a path that led inward, toward her own personal magnetic north. What she’s learned over the last decade and a half has not only deepened the thoughtfulness of her own work but also her appreciation for the role that the discipline of design plays in society today.

Roeder’s studio is located on the imposing Karl-Marx-Allee in Berlin in a Socialist Classical style building that was originally part of a flagship postwar construction project in East Germany. The area is infused with dueling notions of grandeur and decline; historicity and impermanence. The designer herself is a compact, dynamic woman with a ready smile; she watches her surroundings, the market, and the changing fashions with both interest and a certain critical detachment. Informed by her observations and analyses, her designs are equal parts intellect and sensation. Over tea in delicate handle-less cups, we discuss her journey from idealistic design student to the mature artist-designer that she is today.

Looking over the last decade of Roeder’s designs, there is a clear arc; a gradual development from the earlier work that strip forms down to reveal their bare bones, through the later works that emphasize layering. You could say that, throughout, her interest has always been with structures and strata. “I never wanted to lead an architectural, minimalist life, with no decoration,” Roeder says of her early works. The Visual Anaesthesia (2004) series, her graduation project that included the stunning Naked Couch, was often misunderstood as a sort of strict, spartan, and yes, minimalist undertaking. From the photos, it’s easy to understand how this misinterpretation came about. The Naked Couch is built upon a slim, angular framework of chromed steel. But while the skeleton of the piece may seem austere, the deliciously soft, blush-colored leather straps reveal another side all together. In fact, behind the construction of this archetypal daybed lies a personal history; Roeder spent months obsessively combing flea markets and private sales to source the dozens of belts and buckles that she scrupulously documented and customized. In this process—and to Roeder as a maker — authenticity is everything. It’s the sensuality of experience, not asceticism.

Another perfect example; in her studio Roeder shows me the Blue Leather Shelf (2012). Again, it’s an archetypal form. The classic shape is composed of an steel frame and—this is where the surprise comes in—hand-covered in luxurious leather. Free from ornamentation and fussiness, these pieces are nevertheless light-years from a minimalist sensibility. The inviting tactility of the perfectly crafted leather skin over the modernist steel skeleton leaves an impression of subtle extravagance.

Early on, commentators liked to talk about the investigation of things, of objects, of archetypes in Roeder’s work, but she refused to be limited by this sort of categorization. Roeder sees her work as an exploration of stories; she is interested in building narratives and the different perspectives that always coexist within any one story. In her Credenza series, she struck upon a process that combined additivist layering with subtractive techniques to create furniture pieces that encapsulate this notion of stratified structures and layered meaning. The Custom Cabinet (2014) that was produced with Gallery FUMI, for example, uses layers of CNC-milled, ceramic-pearl-blasted anodized aluminum to construct shifting views through to the inner body of the cabinet.

“I don’t like hiding,” says Roeder, “everything should be exposed.” Her approach to this mission though is not as blunt as, say, something in an industrial style; she’s working in that liminal space between skeleton, scaffolding, and the facade. Just how conceptual Roeder’s work can become is perhaps best summed up in the Slow Light Credenza (2010); an ethereal construction of 5068 pieces of 2mm glass strips perched atop tall, steel legs. Literally nothing can be hidden within this completely transparent piece. Slow Light is more of an artwork than a piece of functional design. Or a piece of jewelry, perhaps. Indeed, Roeder speaks about how she thinks of her works as large pieces of jewelry; there’s something about the intrinsic value, the detail, and workmanship of the genre that she finds alluring.

But for a designer who obviously has no shortage of ideas, whose career early on achieved impressive heights (such as the stainless steel and dove-grey suede Nude Facade Credenza she produced in collaboration with Fumi and the Fendi private collection in 2010), why have we not heard more from Tina Roeder in recent years? It’s because she was an early adopter of a strategy that an increasing number of artists and designers are embracing: slowness. “It takes time to be original,” Roeder says as she explains that she views her career in design as a lifetime, rather than a race. She’s spent the last three years just researching and reflecting. “You should think about what you put out there,” she advises, adding that in her opinion some of her colleagues “are too easy with what they put out”.

Roeder is in good company. MoMA Director Glenn Lowry has said “slowness is a virtue, not a problem, when it comes to thinking.” And when, like Roeder, you are more interested in carving out a niche in the pantheon of design greats than having your work seen in every industry event, those periods of deliberate and analytical reflection are crucial. One thing’s for sure; the Credenza series withstands any degree of scrutiny, and Roeder continues to believe in the potential of this ongoing body of work. “My biggest dream is to make just one cabinet a year,” she muses. A far cry from some contemporary designers who work in rapid cycles of quick-fire production and PR.

Such commitment to the art of her work does not come without a price, though, especially in such a fast-moving, trend-based industry. It’s taught Roeder a great deal, of course, to stand outside this constant flow of fashions; difficult and testing lessons. The advice she’d give to her younger self? “Just trust in your own work,” she says; developing that thick skin and confidence is key. For Roeder, looking forward, that means translating her tenacity into something lighter; “I want to be courageous and have fun.” She is embarking on a new collaboration with her partner, New York designer Ward Merrill Hooper, while also continuing to work (slowly and steadily, of course) on the Credenza series, which seems set to become her true legacy. Nearly 15 years after graduating, and a decade on from establishing her own studio, we think Roeder has well earned not only a bit of playful experimentation but also her place in design history.

-

Text by

-

Gretta Louw

A South-African born Australian currently based in Germany, Gretta is a globetrotting multi-disciplinary artist and language lover. She holds a degree in Psychology, and has seriously avant garde leanings.

-

More to Love

Blue Sunday Tide Mugs - Green Edition by Anna Badur, Set of 4

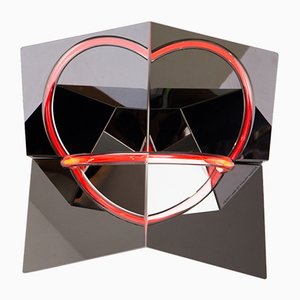

(breaking) Heart Lamp by Philipp Käfer

Drop Plate from the Blue Sunday Series by Anna Badur, Set of 4

Blue Sunday / Pool / Plate by Anna Badur, Set of 4

Tide Mugs from the Blue Sunday Series by Anna Badur, Set of 4

No Cardboard in Brushed Aluminium by Philipp Käfer

No Cardboard in Metallic Blue by Philipp Käfer

Whatever the Weather #01 Pillow by Anna Badur

Beige & Yellow Cotton Bowl by Krupka-Stieghan

Large Beige Cotton Bowl by Krupka-Stieghan

Black & Beige Cotton Bowl by Krupka-Stieghan

Black & Yellow Cotton Bowl by Krupka-Stieghan

Yellow & Beige Cotton Bowl by Krupka-Stieghan

DREI Pendant Lamp by Katrin Greiling for Studio Greiling

No Cardboard in Metallic Pink by Philipp Käfer