A Studio Visit with Formafantasma

Peace of Mind

A quiet thoughtfulness permeates the world of Italian-born, Netherlands-based designers Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin. The two seem to radiate intelligence, warmth, and elegance. Something in their countenance and demeanor gives the impression that they’ve just landed here from another time and place—though whether that’s a romantic past or a more poetically evolved future, or perhaps somehow both, it’s hard to say.

Trimarchi and Farresin are the team behind Formafantasma, one of the most intriguing (and in demand) design studios working today. On a recent Sunday morning, we had the pleasure of visiting the pair’s meditative work-space-slash-residence in Amsterdam-Noord. Set in an unassuming red brick building that once served as a metal stove factory, inside, it’s all exposed beams and light. The designers describe it as “industrial buy intimate.”

Over espresso, sweets, and clementines, Trimarchi and Farresin spoke openly about their studio’s ongoing maturation, their seemingly unending and diverse project list, and their love for their newly adopted city.

Trimarchi comes from Sicily, “one of the few regions [in Italy] still untouched from the industrial production that’s more common in the north.” Farresin comes from Veneto, “where actually the majority of production related to fashion and furniture is happening.” They credit these two very different origins for part of their broad view of the design discipline. The duo first met in undergrad in Florence, and they’ve spent much of the past decade in the Netherlands. Most of their time there has been spent in Eindhoven, first as students (they attended the Master’s program at the Design Academy together as a team; that was where “we learned to ask ourselves the right questions and to conceptually structure a project”) and then later as practicing designers and educators. In 2014, they relocated to Amsterdam, and today, amidst their ongoing design projects, they continue to teach, traveling often back to Eindhoven.

There is no one else like them working in design today. As Formafantasma, they’ve made a name for themselves with intensely research-driven projects ranging from folk craft and material investigations to products and installations, with inspirations spanning an array of places and eras. Their work inhabits a unique space, incorporating the dreaminess of ’90s Dutch design, the rigorous inquiry of contemporary British design, and the intimacy and passion for which the Italians are known. They move between self-driven projects and commissions for world-class galleries and clients such as Fendi, Droog, Lobmeyr, and Hermes; and they are able to hold a compassionate but critical mirror up to whatever topic they take on. Whether they’re exploring 18th- and 19th-century materials and techniques—as they did for 2011’s Botanica series, for which they posited then answered the question: What if the oil-based (plastics) era we’re living in never happened? Which natural materials would we be using instead?—or contemplating the relationships between man and nature or local and global cultures, there’s a unique tension in their work between alternative, imagined realities and the very real historical, political, ecological, and social contexts in which they operate.

Their work is both reasoned and intuitive; it’s also consistently fresh, offering up new ways of looking at both the discipline of design itself and the world at large. The pair themselves have noted: “As designers, every time we begin a new project or investigate a material, our first intention is to question stereotypes and clichés.” Maria Cristina Didero, one of today’s most influential design curators, calls Formafantasma “the most peculiar and surprising creative team on the international design scene.”

The studio’s just come off a very busy—and quite successful—few months that included, among other projects: Anno Tropico, a gorgeous exhibition at Peep Hole in Milan where they presented 18 sculptures celebrating light’s expressive and functional qualities; a window display for Maison Hermès Ginza, incorporating food materials such as rice paper, tapioca, and Himalayan salt; the Delta exhibition at Rome’s Gallerio O, featuring a collection of objects inspired by Rome itself (and for which they spent serious time in the city’s archeological museums); as well as a trio of site-specific installations for the 2016 Lexus Design Award at Salone del Mobile, inspired by the Japanese car brand’s new concept car and the theme of anticipation.

Amidst all the excitement, though, a calm seems to persist. Looking around the studio, the pair notes that their relatively recent move to Amsterdam paralleled a moment of growth for Formafantasma. According to Farresin, “We realized in the moment that as we were moving our plan and the studio were shifting. We had a few years with more work for clients—commercial work and even industrial design projects—and less for ourselves. And we are very happy about it. As a studio, we wanted and we needed to show that we are capable of and interested in different things. In another year, though, we will again [focus on projects] for ourselves [and for galleries].”

Trimarchi adds, “I think it’s of course a different mindset when you work for yourself and for a gallery or [institution] . . . [For example,] we know already in 2017 that we will do a commission for the National Gallery in Melbourne. Working with a museum, the amount of freedom that you have is even greater. So we are really happy to have this coming up. It will be, we already know, a long investigation into metals and the consequences of metal extraction and consumption.”

Farresin offers: “Yes. We want to look not only at the possibilities of metals as materials, but also at the more political and economic consequences of what lays behind extracting metals. And on the other side, we will probably look at e-waste and how that is managed. The process of recycling electronics is crazy; it involves sending containers of stuff [from around the world] to China and Africa, recycling it, then sending it over again—it’s such a process.”

This divided timeline—going back and forth between commercial and privately motivated projects—seems to suit the studio well, affording them not just mental and creative balance but also the quality time they require to do the sort of deep-dive research and reflection that’s come to define their work. This way, ideas can percolate and evolve over time in ways they might not otherwise. As Trimarchi says, “For instance, we did a project on lava about a year ago; it was a project we started three years before, maybe even more. [Even if] you’re not really doing anything [actively], you have it in the back of your mind. And again also for this metal project we are going to do for the National Gallery. We heard about it last year, and it will happen in 2017. It’s [important] to take time to appropriate the project.”

Farresin concurs, saying this larger time frame for self-driven projects allows them more opportunity to really delve into the potential process and the context of each project, “so that the result is as important as what comes before it.” This way they can be also very thoughtful about what they’re putting into the world. “It’s very ethically challenging to be the one who is deciding to add more things, to create more desires for people,” he says. “Because that is what design is used for.”

When asked if the change of location has played a role in their recent inspirations or work, the two are somewhat dubious. Their new studio stands north of the River Ij (pronounced “Eye”), in a relatively quiet neighborhood, separated from central Amsterdam’s hustle and bustle. “We don’t believe that you need to live in a more stimulating place to be creative. I actually think the opposite, that an over-stimulating place kills creativity,” Farresin says. “One of the things that was positive in Eindhoven is that it’s like a white cube for your mind. And I think that’s best; it keeps your mind focused. And now, being in this part of town, we don’t speak Dutch, and we still are in a very silent space, which helps build up a sort of critical mass. I think, for instance, if we were living in Italy, we would not be as sharp—just because there are a lot of influences. A more silent place is better for clarity, which you need for creativity. For us, Amsterdam is a good balance between having a private life and entertainment and cultural events and so on, and then also the silence and the introvert part that is so important for us.”

He goes on: “It’s really strange how this idea of creativity that needs to be fed with so many influences is really not real. Especially now that we have the Internet and this possibility of being constantly overloaded with information.”

So what’s next for Formafantasma? In addition to next year’s Melbourne exhibition, according to Trimarchi and Farresin, the more immediate future includes an exhibition opening in August at the Stedeliljk Museum in Amsterdam, Sportmax’s October fashion week catwalk presentation, a collection of lighting for Euroluce, and involvement with a new design school in Sicily, opening later this year. But in perfect Formafantasma fashion, they’re taking it all in graceful stride, self-aware and ever mindful of their approach.

We can’t wait to watch it unfold.

*This interview has been edited and condensed.

-

Text by

-

Anna Carnick

Anna is Pamono’s Managing Editor. Her writing has appeared in several arts and culture publications, and she's edited over 20 books. Anna loves celebrating great artists, and seriously enjoys a good picnic.

-

-

Photos by

-

Tiziana Krüger

Tiziana is a German-born photographer, based in Amsterdam.

-

More to Love

One & a Half Bench by Antonio Aricò

Wedding Table by Antonio Aricò

Little Stool by Antonio Aricò

Trunk Watering Can by Antonio Aricò

Swing Chair by Antonio Aricò

Teaplof Kettle by Antonio Aricò

Red 3-Legged No 2 Tripod Stool by Studio Wieki Somers

Big Countryside Shelf by Antonio Aricò

Kitchen Utensils by Antonio Aricò, Set of 9

Tasty Chair by Antonio Aricò

Green No 03 Assembled Stool by Studio Wieki Somers

Green No 4 Cardboard Tape Box by Wieki Somers

Elevated Green No 1 Extended Stool by Wieki Somers

Green 3-Legged No 2 Tripod Stool by Wieki Somers

Chinese Stools – Made in China, Copied by the Dutch 2007, Red from Studio Wieki Somers, Set of 5

Red No 04 Cardboard Tape Box by Wieki Somers

Red No 03 Assembled Stool by Studio Wieki Somers

Alphabet Water Glass by Formafantasma

Green 4-Legged No 05 Carpenter Stool by Studio Wieki Somers

Light Pink Mattress Stone Bottle from Studio Wieki Somers, 2002

High Tea Pot from Studio Wieki Somers, 2003

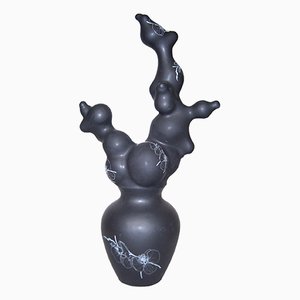

Black Blossoms Vase by Studio Wieki Somers, 2005

White Blossoms Vase Without Holes from Studio Wieki Somers, 2005

Red No 01 Extended Stool by Studio Wieki Somers

Chinese Stools – Made in China, Copied by the Dutch 2007, Green from Studio Wieki Somers, Set of 5